Classical Greek and Roman art

The evolution of classical art, from the idealization of Greek art to the realism of Roman art

Greek art

The concept of "classic"

By classical art we commonly mean the Greek art of the 5th and 4th centuries BC, which had its driving force in the city of Athens. The term “classic”, on the other hand, is a term of Roman origin in the tax sector, and derives from cives classicus, or a Roman citizen who paid taxes, to distinguish him from the peoples of the conquered provinces or countries who did not have the same rights, therefore he was a “chosen” citizen. With this meaning of “chosen”, the term was later used both to indicate the works that could not be missing in a library, and to designate those artists so excellent that they cannot be surpassed, but only imitated. Consequently, if certain authors can only be imitated, as insurmountable, it follows that all the following epochs would be of decline.

According to ancient sources and according to Pliny, Greek art reached perfection in the V and IV centuries BC, and then decayed in the Hellenistic age, therefore the term “classic” retains its original meaning: the period of the V-IV century BC. it is classic as it is perfect, “sublime”, as Winckelmann, the main theorist of “neoclassicism” (an artistic and cultural movement of the eighteenth century, which shared and took up this vision of ancient art) would say.

Therefore, if for rigor we consider as classical only the Greek art of the 5th and 4th centuries BC, all the following eras are not classical eras, but classicisms, that is, periods of imitation of the classical and, therefore, a large part of Hellenistic production and almost all of Roman production would only be imitations. The Renaissance, which has more “recreated” than imitated the conditions of classical art, is a completely exceptional case. Over time, objective historical analysis has led us to keep the definition of “classic” for the 5th-4th century BC, but only for convenience, without any judgment.

SEE ALSO: Beauty from Voltaire to Winckelmann

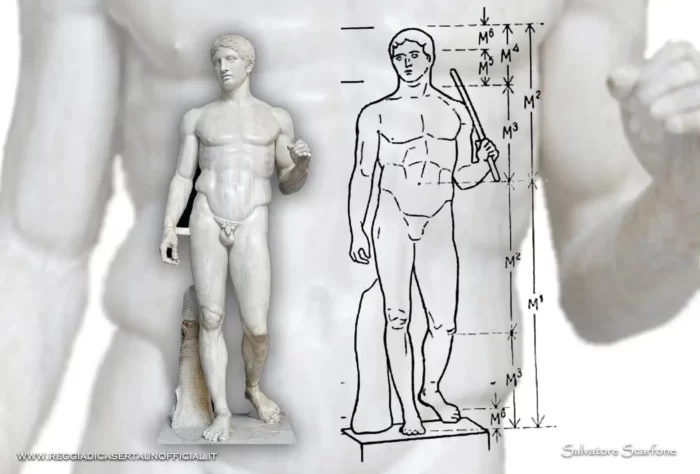

The Kànon

In Greek culture the creativity expressed, for example, in literature, music and art, was subject to the Kànon (canon, rule), a series of rules considered a guarantee of perfection, which were observed by the artist, even if not strictly , on the other hand, they were later rejected as limiting. The canons, therefore, were therefore continually revised and corrected, so much so that over time they came from schematic forms to naturalistic forms. The transition from the schematic and geometric form to the realistic form is considered by some scholars to be the most important moment in the history of art.

But even on this “naturalism” it is necessary to clarify. It is true that classical artists tried to reproduce the human body realistically, but it is also true that they wanted to discover, and reproduce, its constant proportions. This is the most typical trait of their works. : the individual parts of the body are perfectly realistic, but the totality is not that of a person, but the representation of the ideal human body.

Therefore, in architecture as in sculpture, the canon established the proportions between the various parts of the whole so that the work would be harmonious, that is, perfect. A sort of schematized realism, then. The idealization of reality gave the artists an awareness of the duration of their works over time.

From geometry to schematized realism

In classical Greek art there are two periods:

- that between 450 and 400 BC, dominated by the Fidiac and post Fidiac style,

- that of the 4th century BC, dominated by the three great sculptors Skopas, Praxiteles and Lysippos.

Therefore, the personality of Phidias stands out, already celebrated by the ancients as the greatest artist of all time, whose work marks the apex of classical art. In the sculptures of the Parthenon, which he designed when not directly executed, Phidias knows how to interpret the political, ethical and religious values of his time in works of great vitality and suggestion.

A more careful observation of the human body leads to better highlighting of the anatomical details and to a greater plastic yield, all according to proportional rules that Polykleitos of Argos established in a theoretical treatise. Despite their importance, these rules were never applied rigidly, indeed, especially later, a greater naturalness and expression of feelings were sought, with the latter aspect dominating in the fourth century BC. and which will have notable developments in the Hellenistic period.

In this phase, the search for movement also continues, but in other words: no longer the figure in balanced dynamic equilibrium on the central axis, but in unbalanced positions when not even in accentuated torsion to underline its drama. This is the case of Skopas, who creates highly expressive, sometimes dramatic figures. Praxiteles, his contemporary, invents sensual figures of gods and goddesses.

This transformation demonstrates a profound change in Greek history, and is explained by the profound crisis which, in the fourth century BC, marked the Greek decline in favor of Macedonia, and therefore the decline of Athens. In this phase the figure of Lysippus dominates in the sculpture. He takes up the canon of Polykleitos to modify it profoundly in terms of greater fluidity and naturalness, abandoning the search for the ideal form in favor of pure realism. This new concept, as well as Lysippos’ activity as a portraitist, created the basis of the nascent Hellenistic period.

The proportion in the architecture

The architects were the first in Greece to establish construction rules, which were always applied, but still allowing variations for practical or aesthetic reasons: lines were bent that should have been straight to correct perspective deformations; the contours of pedestals, cornices, columns were slightly curved.

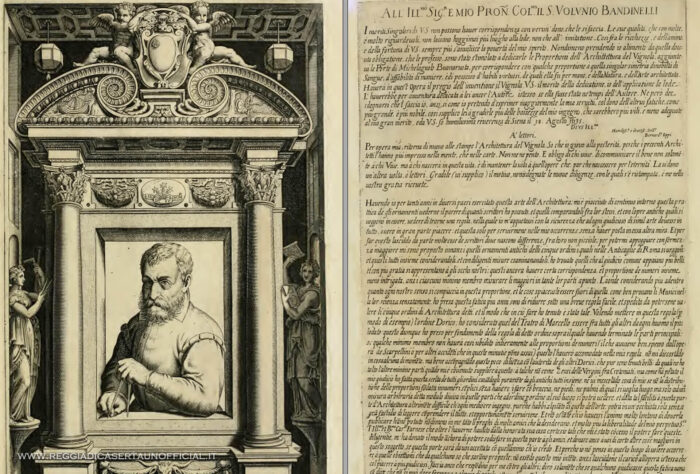

The canon of classical Greek architecture had a mathematical basis. For Vitruvius:

“Composition depends on symmetry, the laws of which architects should strictly observe. Symmetry is created by proportions … we define the proportions of a building by means of calculations relating both to its parts and to the whole, in accordance with an established model ”.

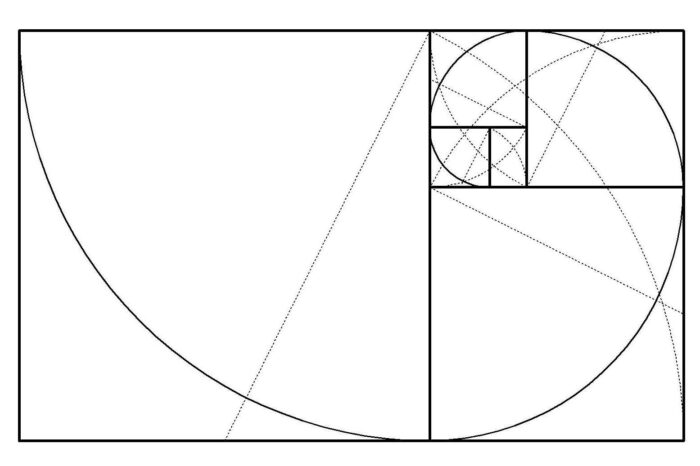

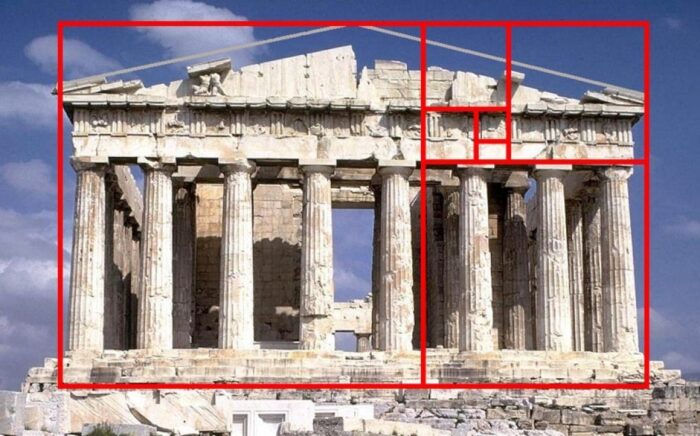

The Golden Ratio

Considered together with the Pythagorean theorem one of the two treasures of geometry, the golden section, represented by the number 1.618, is a mathematical proportion between two different lengths that has always been considered as a guarantor of beauty and harmony. Present in architecture since the time of the Egyptian pyramids, it can even be found in botany, physics, zoology, painting and music!

To create a rectangle according to the golden rule, multiply the smaller side by 1.618.

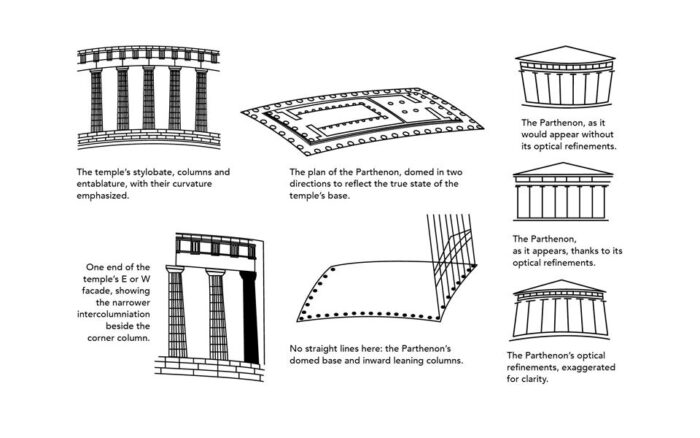

Optical corrections

Ictino wrote a treatise on the Parthenon, in collaboration with the architect Karpion, which testifies the attention of the designers to every aspect of the work. Perhaps the most surprising chapter of this treatise concerns the optical corrections that were made, during construction, to the various ribs of the building.

- The columns of the Parthenon are designed in a particular way: Doric, but close in slenderness to the Ionic type, they are equipped at about one third of the total height with an imperceptible bulge, called éntasis, which serves precisely to correct the optical distortion for which the eye perceives a row of perfectly cylindrical columns as slightly concave inwards. Entasis causes them to be perceived as slightly tapered cylinders, that is, narrower at the top.

- For a similar principle, Ictino also corrects the sides and the architrave of the temple, which, although seeming perfectly straight, is actually slightly rounded. These are differences of a few centimeters over many meters in length, but if their absence would perhaps be noticed, while their presence is absolutely imperceptible.

The Parthenon as an "idea" of the temple

If from a certain point of view Ictino seems to simply want to improve a fairly traditional building, in reality it radically transforms it, creating a reference model that is in a certain sense eternal. Like Polycletus’s Doryphoros, and the same sculptures by Phidias that adorned it (still existing although dispersed throughout the world), the Parthenon lives a double life: as a royal building on the Acropolis of Athens, and as an ideal reference of architectural beauty.

Roman art

The evolution of the classical Greek model

When it comes to classical art, one immediately thinks of Greek art of the 5th and 4th centuries BC; however, in a broader sense, the term also includes ancient art that was produced in Rome, starting from the centuries immediately preceding our era, up to the entire second century after Christ. Of course, looking closely at the ways in which the Romans took up classical art, one might think of their artistic production as an imitative production, rather than “really” classical. The Romans in fact began to “collect” (so to speak, because in most cases it was booty captured in war) Greek art, after the capture of Corinth, in 146 BC; even if in some way a “Greek” artistic language or strongly influenced by the Greek ways had already penetrated into Rome through the nearby Campania and through the mediation of the Etruscan civilization.

Later, however, Rome did not limit itself to acquiring original Greek art or art produced in the great Hellenistic centers, but imported artisans and began a production of both copies and typically Roman subjects through a formal Greek-Hellenistic mediation. The model of the Hellenistic portrait, for example, enters Rome very early, but it is above all under Augustus that the choice of a classicist declination somehow receives a license of officialdom.

The meaning of Augustan classicism

Already during the first century BC, a retrospective trend had manifested in Athens which promoted artistic models inspired by the first classicism if not even the “severe style”. Augustus seems to conform to this type of taste, which if for the Greeks of the time had to represent the rediscovery of tradition and the golden age of their civilization, to the emperor it must have seemed the most suitable instrument to underline the existence of a tradition Roman, simple in itself, but now vested with a dignity that is also formal, which placed Rome on the same level as all the most ancient and refined civilizations that overlooked the Mediterranean. We would risk misunderstanding the Augustan message if we did not consider this vaguely nostalgic aspect, which through a virtually “dead” style also recovered customs and habits of an ancient Rome that was in danger of disappearing. See in this, in the Augustan monuments, starting from the Ara Pacis, the attention to ceremonial rituals, or to sacrifice, which is particularly highlighted in the official iconographies.

As for the panorama of painting, Pompeii, with its thousand faces, gives us an idea of this aspect of Roman art, in its various levels of quality. But we can also think of an “almost” official monument like the Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli to realize the Roman taste. This imperial residence was in fact adorned, one could say, with a kind of “anthology” of classical sculpture, from Polykleitos to Phidias, from the Erechtheion caryatids to the most famous Hellenistic Venuses. With a particularity, which today would make an art lover smile or horrify: none of the works exhibited in the emperor’s villa was an original, they were all copies and imitations.

This detail should make us reflect on the meaning assumed by the work of art in antiquity: a precious and elaborate object, but devoid (at least to a certain extent) of that magical aura that makes each original unique and devoid of any interest for us. (if unscientific) any copy or imitation. Evidently a refined emperor like Hadrian did not disdain good imitations of now mythical works.

The characteristic realism and the sense of history

Naturally, it is not possible to reduce the problem of classicism in Rome to a mere question of imitation. Quite the contrary is true: the great Roman art, while continually drawing on Greek or Hellenistic formal models, transforms them and bends them to its own needs, Finally inventing its own language that is peculiar and easily distinguishable from the Greek or Hellenistic one. Otherwise, the great monuments and great achievements of Trajan and Antonine art, which constitute the most typical and highest quality original creations of Roman classicism, would be inexplicable. However, it is a classicism that is losing its Greek flavor, to acquire a new, absolutely Roman one. In this sense, it is perhaps with the art of the so-called “decadence” that Rome will leave us its most original creations, detaching itself from the classical world and laying the cultural foundations of the nearing Middle Ages.

Roman classicism introduces the sense of history into its horizon. Compared to the Greek world, which alludes to reality through the filter of myth, the Roman world seeks a new type of realistic representation. Particularly under Augustus, for example, the image of sacrifice or worship becomes popular, more than mythical representation, through which particular recurrences are remembered: concrete images of how the people express their religiosity. The cult, rather than the mythical episode from which this derives, thus becomes the element of defense of tradition, of Roman costume. Even in the case of wars or military victories, to which the Greeks alluded for example through the representation of the Giants attacking Olympus, or of the wars against Amazons or Centaurs, the Romans camp realistic representations of fights, coming to make certain military campaigns, exhaustive reports (see the whole picture of the wars in Dacia told by Trajan’s Column). These representations of historical episodes show how the characteristics of classical realism change in the Roman world: not only a representation of ideal nature, but an attempt to tell in real terms.