Beauty from Voltaire to Winckelmann

Two apparently opposite visions of beauty

The concept of Beauty in two opposing visions of two of the greatest intellectuals of the eighteenth century, Voltaire and Winckelmann

INDEX

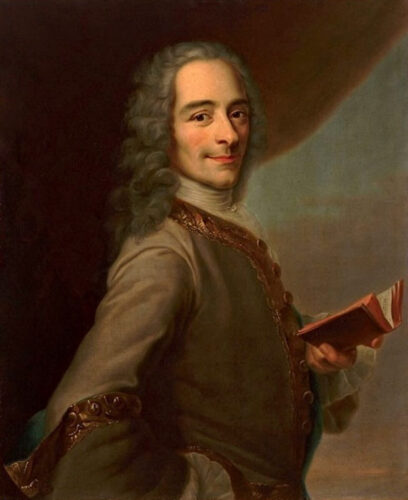

Voltaire

Voltaire biography

Voltaire – Paris, November 21, 1694 – Paris, May 30, 1778)

Voltaire was a French philosopher, playwright, historian, writer, poet, aphorist, encyclopedist, fairy tale author, novelist and essayist.

Voltaire’s name is linked to the cultural movement of the Enlightenment, of which he was one of the promoters and main exponents together with Montesquieu, Locke, Rousseau, Diderot, d’Alembert, d’Holbach and du Châtelet, all gravitating around the environment of the Encyclopédie. Voltaire’s vast literary production is characterized by irony, clarity of style, liveliness of tone and polemic against injustices and superstitions. Deist, i.e. follower of natural religion which sees divinity as extraneous to the world and to history, but skeptical, strongly anti-clerical and secular, Voltaire is considered one of the main inspirers of modern rationalist and non-religious thought.

Voltaire’s ideas and works, as well as those of the other Enlightenment thinkers, have inspired and influenced many contemporary and subsequent thinkers, politicians and intellectuals and are still widespread today. In particular, they influenced protagonists of the American revolution, such as Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, and of the French one, such as Jean Sylvain Bailly (who held a fruitful epistolary correspondence with Voltaire), Condorcet (also an encyclopedist) and partly Robespierre, as well as many other philosophers such as Cesare Beccaria, Karl Marx and Friedrich Nietzsche.

Beauty for Voltaire

Voltaire (1694-1778) wrote in his Philosophical Dictionary (1764), under the heading “Beauty – Beauty”:

Ask a toad what beauty is, true beauty, to kalòn. He will answer you that it is his female with two big round eyes protruding from the little head, a broad and flat muzzle, a yellow belly, a brown back. Question a Guinea negro; beauty for him is black, oily skin, sunken eyes, a flat nose.

ask the devil; he will tell you that beauty is a pair of horns, four claws and a tail. Finally consult the philosophers, they will answer you with a rant; they need something that conforms to the archetype of beauty in itself, al to kalòn.

One day I was witnessing a tragedy next to a philosopher «How beautiful she is!», He said. “What do you find beautiful about it?” I asked him. “It is that the author,” he said, “has achieved his purpose of him.” The next day he took a medicine which did him good. “It has accomplished his purpose,” I told him; “Here’s a nice medicine!” He understood that a medicine cannot be said to be beautiful, and that to give something the name of beauty, it must arouse admiration and pleasure in us. He agreed that the tragedy had inspired those two feelings in him, and that the to kalòn, the beautiful, lay in it.

We made a trip to England: the same tragedy was given there, perfectly translated; it made all the spectators yawn. «Well», he said, «the to kalòn is not the same for the English and for the French.» After much reflection, he concluded that beauty is very relative, just as what is decent in Japan is indecent in Rome, and what is fashionable in Paris is not fashionable in Beijing; and saved himself the trouble of composing a long treatise on beauty.

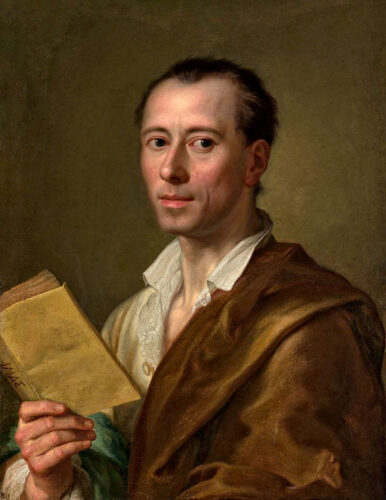

Winckelmann

Biography of Winckelmann

The beauty for Winckelmann

[…] The ability to feel the beautiful has been granted by heaven to all reasonable creatures, but in very different degrees. Most people act like the light particles which, all attracted in the same way by a crumpled electric body, soon fall from it; therefore their sensitivity is brief like the sound of a short string. The beautiful and the mediocre have the same value for them, as the agreeable and the common have the same value for a being of average education. In some this capacity exists in so minute a degree as to suggest that nature ignored them in distributing it; and of this sort was a young English aristocrat who gave no sign of life when, strolling with him in the carriage, I made a speech to him on the beauty of the Apollo and other statues of the first order. The sensitivity of Count Malvasia, author of the Lives of the Bolognese painters, must have been of a similar temper; this chatterbox calls Raphael the Urbino pottery maker, referring to the vulgar legend that this god of artists painted vases that then the ignorance beyond the Alps considered precious, and he dares to claim that the Caraccis spoiled by imitating Raphael. On such beings the true beauties of art act like the aurora borealis which illuminates but does not warm; one could almost say that they are of that sort of: «creatures which – as Sancuniatone says – have no feeling». Even if the beauty in art were only a face, as among the Egyptians God is all eyes, even if concentrated in a single part, it would not move their souls.

The fact that this feeling is rare, could also be attributed to the lack of writings teaching the beautiful, since from Plato to our times such writings on the beautiful are generally without erudition and of little content. Some moderns have wanted to deal with the beautiful in art without knowing it. I could give new proof of this with a letter from the famous Mr. von Stosch who is the greatest antiquarian scholar of our day. In it, sent to me at the beginning of our correspondence, because we did not know each other personally, he wanted to instruct me on the ranking of the best statues and on the order I had to observe in examining them. I was amazed when I saw that a scholar so versed in ancient things considered the Vatican Apollo, which is the maximum expression of which art, inferior to the sleeping Faun of the Barberini Palace, which represents a wild nature, to the Centaur of the Villa Borghese, which is far from every ideal beauty, to the two old Satyrs of the Campidoglio and to the Ram of the Giustiniani collection of which the only beautiful part is the head. Niobe and her daughters, who constitute the perfect model of female beauty, occupy the last place in this ranking. I persuaded Mr. von Stosch of his mistake, and he confessed to me to justify himself, that he had seen the ancient works when he was young, in the company of two artists from beyond the Alps who are still living, and he had based his judgment on their judgment until then. […]

The ability to understand beauty awakens and matures through a good education; if education is neglected it manifests itself with more difficulty, but it cannot be suppressed as I myself know from experience. However, it develops better in large cities than in small ones and more by practice than by erudition: since knowing a lot, the Greeks say, does not generate a healthy intellect, and those who have become famous only for their erudition in ancient things, do not for this reason they have come closer to this ability to feel. The Romans neglect to cultivate this feeling which should develop and mature sooner in them than in others; they do not possess it, because men are similar to hens who leave the closest grain to take the furthest away; what we always have before our eyes usually does not arouse any desire in us. A well-known painter still lives, Niccolò Ricciolini, a native of Rome, a man of great talent and very learned even in things that do not concern his art, who a few years ago, at the age of seventy, saw for the first time the statues of the Villa Borghese. He studied architecture in depth, and although he traveled around Rome in every sense as a passionate hunter, he never saw the tomb of Cecilia Metella, wife of Crassus, which is one of the most beautiful ancient buildings. For these reasons, apart from Giulio Romano, there are few famous artists born in Rome. Most of those who acquired fame in Rome, both painters and sculptors and architects, came from outside, and even today there is no Roman who distinguishes himself in art.

In early youth this capacity is, like any other inclination, wrapped up in vague and obscure feelings and manifests itself as a wandering itch of the skin, which by scratching one never gets to the precise point. It is found more easily in well-born boys than in those who are not, since we are generally more interested in knowing how we are made according to character and feeling than according to education: a sensitive heart and a docile character are signs of this ability. . It shows itself more clearly when, reading an author, the soul feels tenderly moved by passages that do not touch an uncultured soul; this would easily happen with the oration of Glaucus and Diomedes, a moving comparison of human life with trees that, stripped by the wind, sprout again in spring. When this feeling is lacking, the understanding of the beautiful is preached to the blind, like music to the deaf. An even more evident sign in youngsters who do not grow up in contact with art, nor are they destined for art, is a natural inclination for drawing, which is as innate as that for poetry and music.

Since, then, human beauty must be represented by a general idea in order to be understood, I have observed that it is not easy to find a natural, general and lively feeling of beauty in art in those people who are fascinated by female beauty and little or nothing are touched by the beauty of our sex. For them, in the art of the Greeks the beautiful will remain incomprehensible, since there are reproduced more beauties of ours than of the other sex. More feeling is required for the beautiful in art than for the beautiful in nature, because in art the beautiful is as tears are in the theater, without pain and without life, and therefore it must be provoked and compensated for by the imagination . But as the imagination is much more fervent in youth than in mature age, it is necessary that the capacity of which we speak should be exercised early and be directed to the beautiful before the age arrives in which, frightened, we must confess that it lacks. But when someone admires the ugly he can not always deduce that he lacks the ability to feel the beautiful. For just as children who are allowed to get too close to everything they want to see learn to look one-eyed, so the sentiment can become spoiled and false if the subjects contemplated in their youth were mediocre and bad. In places where art cannot reside, I remember hearing talented people debating the pronounced veins of the awkward figurines carved into our cathedrals, and this to boast of their own taste: they had seen nothing better and were doing like the Milanese who prefer their Cathedral to St. Peter’s in Rome.

[…]

The organ of this feeling is the external sense and its seat is the internal sense: the first must be exact, the second sensitive and delicate. However, the accuracy of the eye is a gift not granted to everyone, like fine hearing and acute sense of smell. One of the most famous contemporary Italian singers possesses all the qualities of his art except a right ear. Many doctors would be more skilled if they had a more refined tactile sense. Often our eye is deceived by optics and often by itself.

The exactness of the eye consists in seeing the true shape and true size of the object, and the shape includes both color and form. All artists do not see colors in the same way, because they reproduce them differently. To demonstrate this, I do not want to refer to the bad coloring of some painters, for example that of Poussin, since negligence, bad method and incompetence are partly the cause; I am referring to what I myself have seen done by some painters, in whom I have been able to notice that they are unable to recognize the deficiency of their colouring. My argument rests principally on painters who, though they are good colourists, nevertheless have some faults; I can mention the famous Federico Barocci in this regard, whose meat is always greenish. He had his own method of painting the background of the nude in green, as can be clearly seen in some of his unfinished paintings in the Albani Gallery. The sweet and pleasant way of coloring in the works of Guido Reni, and strong, gloomy and often sad in those of Guercino, is even revealed in the faces of these two artists.

No less different are the artists in representing the true aspect of the form, and we infer it from the imperfection of their figures. Barocci can be recognized by his strongly inclined profiles, Pietro da Cortona by the small chins of his heads and Parmigianino by the long oval of the faces and long fingers. However, I do not want to affirm that, when all the figures seemed consumptive as before Raphael, and when they became hydropic in Bernini’s time, the artists all lacked the accuracy of the eye; since in these cases the fault consists in having chosen and blindly followed a false system. The same goes for proportions. We see artists getting parts wrong even when they paint portraits that they can look at calmly and at ease; in some the head is too small or too large, in others the hands are disproportionate; sometimes the neck is too long, sometimes it is too short, and so on. If the eye does not acquire a sense of proportion through years of continuous exercise, there is no hope that it will ever acquire it.

Now, given that what we notice even in expert artists is caused by a lack of precision of eye, it is clear that we will see this even more frequently in people who have not exercised this sense. But if the disposition for accuracy exists, this develops with exercise, as can even happen with sight: Cardinal Alessandro Albani is able to distinguish coins just by touching and feeling them and to say which emperor they represent.

If the external sense is right, we can hope that the internal one is just as perfect: since it is a second mirror in which, through the profile, we recognize the essential features of ourselves. The internal sense is the representation and formation of impressions received from the external sense, that is, what, in a word, we call feeling. But the internal sense is not always proportionate to the external one, that is, its sensitivity does not always correspond to the accuracy of the external sensitivity, because the action of the external sense is mechanical, while the action of the internal sense is intellectual. There may therefore exist perfect draftsmen who have no feeling, and I know one; but they are only capable of imitating the beautiful, not of taking stock and realizing it. […]

This internal sense of which I speak must be ready, delicate and imaginative. It must be prompt and quick, because first impressions are the strongest and precede reflection: what this makes us feel is weaker. The generic feeling that drives us towards beauty can be obscure and without reason, as are all first and immediate impressions, as long as the examination of the object admits reflection, accepts it, indeed requires it. Anyone who wanted to pass from the parts to the whole in this field would demonstrate the brain of a grammarian and would hardly be able to awaken in himself a feeling of the whole and an ecstasy.

This sense must be more delicate than impetuous, because beauty consists in the harmony of the parts; the perfection of these consists in a gentle ascent and descent, and therefore acts uniformly in our feeling, guiding it with a gentle hand and not with sudden jerks. All impetuous sensations touch the immediate without dwelling on the mediated, the feeling should instead arise as a beautiful day arises from a soft dawn. Impetuous feeling also harms the contemplation and enjoyment of the beautiful, because it is too brief: it leads suddenly to the point that it should only be reached gradually. It seems that also for this reason the ancients clothed their ideas with symbols, thus hiding their meaning to leave the intellect the pleasure of reaching them gradually. Therefore hot-headed and hasty heads are not very apt to feel the beautiful. […]

The third property of internal feeling mentioned by me, consisting in a lively imagination of the beautiful contemplated, is a consequence of the first two and must not be separated from them; but, like memory, its strength grows through exercise, but contributes nothing to the other two. This quality, more than in a painter of great skill but devoid of feeling, can be lacking in a man of refined feeling, so that the image imprinted in his mind is generally lively and clear, but it weakens if he wants it recall exactly piece by piece. The same happens with the image of the distant loved one and with almost all things; looking too much for the parts makes you lose the whole. But a painter who works only mechanically and who paints portraits preferably, can increase his imagination and strengthen it by the necessary exercise, so that the image with all its details can remain impressed in it and every part can repeat itself in the memory.

This ability is therefore to be appreciated as a rare gift from heaven which has thus made sense suitable for enjoying beauty and life itself, of which happiness consists in the stability of pleasant feelings […].

External Link